In the mid-1980s, sentencing in federal criminal cases became a partly mathematical process, when Congress formed the United States Sentencing Commission. The goal of Congress was to create a system in which defendants were fairly sentenced based on the facts of their cases, and to avoid unfair variations based on inappropriate factors.

The idea was simple — if a person embezzled $100,000 from his employer in California, he should probably be sentenced to a similar term of imprisonment to a person who embezzled $100,000 in Maine. Certain things should not make a difference, either implicitly or explicitly, including gender, race, age, the period of the crime, the method of the embezzlement, and so forth.

It seemed that some things certainly should make a difference, including the amount embezzled, whether the defendant took advantage of a particularly vulnerable victim, whether there were many victims, whether the defendant played a large or small role in the crime, whether a bank was put at risk, whether violence was involved, whether the defendant accepted responsibility for his actions, and very importantly, whether he had committed previous criminal acts.

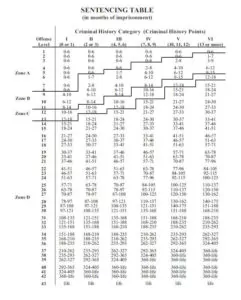

The system which developed was a point system which measured two things: the seriousness of the offense and the severity of the defendant’s criminal history. With these two numbers the sentence could be calculated by using the sentencing table, which was a sort of grid:

On the year 2000 Table, the intersection of Offense Level 16 and Criminal History Category III is 27-33 months, and that would be the Guidelines Sentence. A judge would probably sentence the defendant somewhere in that range.

Over the last decade the U.S. Supreme Court has made it clear that the Guidelines are advisory, not mandatory, and that judges should look at all sorts of additional factors before pronouncing sentence, but the Guidelines still are very important in calculating a sentence in federal court.

This is a simple introduction to a complex process — each year’s Guidelines Manual runs well over a thousand pages and this post is less than a thousand words — when you consult with an attorney, he or she can help you to understand how the Federal Sentencing Guidelines will impact your matter.

This blog post was written by Allan F. Brooke II. Allan F. Brooke II has degrees in physics, astronomy, literature, theology, and law. He graduated from Vanderbilt University in 1979, and Dallas Theological Seminary in 1986. In 1992, Mr. Brooke graduated with honors from the University of Texas School of Law, where he was an Executive Editor of the Texas Law Review and an Associate Editor of the American Journal of Criminal Law. His legal publications include articles on commercial damages and Supreme Court history and, as editor, a book on Texas litigation practice. Mr. Brooke interned with the Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court, the Honorable Thomas R. Phillips, and came to the Bedell firm in 1993 after clerking for the Chief Judge of the Eleventh Circuit, the Honorable Gerald B. Tjoflat. He is a member of the Florida and Texas bars, and is admitted to practice in the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. He formerly served on The Florida Bar’s Committee on Technology, and is a past member of the Executive Committee of the Chester Bedell Inn of Court. He has repeatedly been listed in The Best Lawyers in America and similar publications. Mr. Brooke’s current areas of concentration include white-collar criminal defense, appellate litigation, and complex commercial litigation. Mr. Brooke speaks and teaches frequently on theological and literary topics. He and his wife, Katherine, have five children.